Pieter van Marken

Pieter was a teenager during the war. He lived with his parents a short distance from Schiphol airport in Holland. Pieter wrote down his war memories a short while ago so it would be there to read for his children. The following is a short version of his memoires.

Pieter was a teenager during the war. He lived with his parents a short distance from Schiphol airport in Holland. Pieter wrote down his war memories a short while ago so it would be there to read for his children. The following is a short version of his memoires.

Growing up before the war

I was born in 1928 in the Prinsengracht hospital in Amsterdam, which was closed down some years ago, like many other relatively small hospitals in Holland. This trend was meant to result in a more efficient hospital service, by creating large, manager run, hospitals. Before I was born my parents lived in the the Dutch East Indies in Java. This was a Dutch colony at that time. My father, after whom I was named, took long overseas leave to travel to Holland. An older brother, their first child, who was called Richard Anthony, had died of malaria when still a baby. Mother was worried and wanted me born in a country where health conditions were better than in the tropics. We went back to Java but returned to Europe in 1931 we went to my mother's place of birth., Brussels. She was a Wallon, a French speaking Belgian and the first language I actually spoke was French, my mother tongue. In 1932, we went to Holland and my parents moved into an apartment at the Stadionweg in Amsterdam.

The war years

I don't remember much of the outbreak of war on May 10 in 1940, except that it came sudden and unbelievable as dozens of Heinkel 111's bombed nearby Schiphol airfield after they had bombed the army barracks, killing many unsuspecting and ill prepared and untrained Dutch soldiers. The war was over in a matter of days and the Netherlands surrendered to the Germans after they had bombed and virtually obliterated the centre of the city of Rotterdam.

We had moved to Amstelveen after father had accepted the post of managing director of a factory - Philips van Houten - making vitamins in chocolates in a town called Weesp. I played cricket and hockey on a field which was covered with long poles stuck into them, to stop Allied gliders landing unscathed, which were put up there by the Germans.

I spent the war years in Amstelveen and I remember watching the Allied planes go over, sitting with my mother on a window sill at night. We did not get much sleep but you could not sleep much anyway with the droning of the aircraft, the racket of the ack ack, going off loudly in the neighborhood, the sound of the explosions in the air and the shrapnel from the exploding grenades which came whizzing down in the night, crashing onto the roof. I had a good collection of shrapnel. Can't imagine what happened to it. My mother and I once saw a plane explode in a thousand sparks, caught in a bundle of searchlight beams. In later years, Allied planes dropped window-metal foil strips which, when dropped, provided an echo, meant to confuse radar location equipment. Clouds of these strips were dropped and the ground was subsequently covered with thousands of those metal-foil strips. In 1941 or it could have been 1942, a column of German petrol tankers, covered in camouflage netting, was parked and nicely hidden in the Kalfjeslaan, a lovely tree lined lane nearby and there was mayhem when Allied bombers bombed the Kalfjeslaan. Unfortunately, or perhaps not, they missed by a hundred meters or so. The bombs fell harmlessly in the adjoining meadow.

I practiced pyrotechnics and I made "bombs" with potassium, which I bought from our local friendly chemist where my mother had an account and sulphur, scraped from matches. I filled empty 9 mm shells - don't ask where I got these from - with this mixture and laid them down on a fire I built underneath with the same mixture until they went off with a good bang.

Once I decided that it was a good idea to scare a member of the German friendly Socialist Party N.S.B., who lived near the school. I let off one of my bombs on his window sill. Of course, he caught me in the act and handed me over to the police. Generally speaking, the Police were not to be trusted, but the policeman who came to collect me, did not hand me over to the German police as instructed, but kept me for a few hours at the Overtoom police station in Amsterdam and let me go after a sermon. My parents, who had meanwhile been told wild stories that I had been picked up by the German police, the Grüne Polizei, were suitably grateful. Of course, the Grüne Polizei were a bit like the M.P. Not too bad. The real bastards were from the SD "Sicherheits Dienst" and their Dutch collaborators and the Gestapo, of course.

I remember crying in the early years of the war, seeing three R.A.F. Bristol Blenheims being shot down. The crews parachuted down. My wartime adventures included the time when a plane, I think it was an American flying fortress, was shot down over Amsterdam. I followed the plane on my bicycle as it came down and saw it crash between houses in an Amsterdam street. It brought down suspended electric and telephone wires and God knows what else, but the pilot had managed to avoid the houses and crashed down in between the houses. He was a hero. I can't remember if any of the crew escaped or if the rest of the crew had bailed out. Lamp posts were mown down. A total shambles. I managed to get myself in a sort of picket line, arm in arm, to keep spectators away from the fire and possible explosions of ammunition so that I had a first class view of the disaster.

At the end of the war, there always were two Allied planes in the air watching any traffic on the ground.

After the railway strike, which I will later comment on, very few trains were running and when they did, they were strafed as and when they appeared. They also strafed anything else that moved, even carts. When they spotted something, they came hurtling down, guns blazing and rockets whizzing. I think they were usually an American P-38 Mustang and a R.A.F. Mosquito. I am not sure.

Once, I was letting my, or rather our dog out, a lovely large black poodle called Gypsy, in the nearby forest to be, then called the "Bosplan" The "Bosplan" was just a number of young trees which had been planted a few years before the war, to create a future "Bos", or forest, which it now is.

Suddenly, I saw a Mosquito, quite silent at that distance, coming straight for me. Closer by,

it let go of it's rockets which came whizzing over my head, slamming into a car parked between some houses and noisily exploding. It eventually turned out that the car they were shooting at was one of "ours". One of the houses there, belonged to friends of the family.

I became ill in 1943, fifteen years old. I started off with diphtheria, followed by pneumonia and then pleurisy. Finally I also had jaundice, Hepatitis A. My father managed to get some food for me, like fruit and sugar, buttermilk and cream, helping me to recover. I was skin over bones. I have hated drinking buttermilk ever since. I didn't mind eating grated apple drenched in cream and with a liberal coating of that rare commodity, sugar.

The jaundice put an end to a fast recovery and my intake of fatty foods. We lived not far from the national airport, Schiphol. In 1943, the Allies decided that the Luftwaffe should be attacked in preparation for the coming invasion of Europe. Schiphol was one of the most heavily defended German airfields and was attacked three times. On Sunday October 3 1943, 71 American B-26 Marauders of 386 Bomber Group, bombed Schiphol. Fighter cover in the form of R.A.F. Spitfires, swooped to shoot down the Messerschmitts, which took off to attack the bombers. A Professor, who attended me as a specialist with our GP, got very excited when two of the German fighters were shot down by Spitfires as they took off. One, trailing smoke, came over our house after being shot down and crashed in the nearby Bosplan, close to the hockey fields, where we played. The professor ran from one side of the house to the other, watching this exciting spectacle, while some of our neighbors were cheering outside. Some of them had even climbed on the roof. Very dicey, of course. I did not see much of it myself, although I was well enough to see some of the action out of the window of my bedroom and I could waddle about bit.

The Germans hit back at the Dutch to make them pay for the railway strike. The transportation of food had ceased completely for six weeks. On September 27. the first signal from occupied Holland that food was becoming a problem reaches London. There was only food left for several weeks in Western Holland. From that moment, the rations became smaller and smaller. The South East of the Netherlands had been liberated at that time but there was great suffering north of the rivers, in particular around Amsterdam, as there was no food. We had a pretty rough time then. My brother Ben had been to Germany as a forced laborer on the German Swiss border at the Rhine; he worked on a dam building project called "Hochtief A.G". He fully expected to swim across the Rhine to escape into Switzerland. Wishful thinking, of course, he never made it across, but he did try, but found himself thrown back on the same side by the currents. He was lucky not to be caught by the Germans and he was repatriated when he shammed a concussion.

We had a hiding place built in our house, behind a movable bookcase where we, or rather Ben, could hide. when the Germans came on a so called "razzia", a raid. Any man caught in a raid could be sent to Germany into forced labour. But the men were also used for local labour, like repairing the runways at Schiphol Airfield. Under 17 you were still fairly safe although the Germans would probably have sent me home anyway, as I hardly looked like a laborer, skin and bones as I was. Also, I could go on "hunger" trips on my bicycle, to get food. without being picked up in a "razzia". At the end of the war, we suffered real hunger, as food supplies dwindled to nothing. We were also very cold. The winter of 1994/1945 was in particular very cold.

There was no heating or electricity. There was no coal to keep the central heating going. We had no lights except by having Carbide powered lights. I am not sure how they worked. Sort of Carbide gas filled lamps. I knew Carbide, of course. I used to explode the lid off a big can, after having put a few lumps of Carbide into it. A small hole in the can, a bit of water and fire! A big bang followed and the lid flew off. Wonderful toy for a little boy like me. We had moved father's D.K.W. to another empty garage a couple of streets away, taking the wheels off, and putting the car on wooden blocks. We hid the wheels in our attic. One day, the German "Grüne Polizei" came past and took mother to the garage where they had found our car perched on blocks. They wanted to confiscate the car They asked her where the wheels were, but she never told them. Said she did' nt know.

I had a crystal radio set, to listen to the BBC and to messages from "Radio Oranje" and the government in exile in London. It was hidden under the floorboards on the top floor of our house. It fitted in a cigar box and consisted of a coil, a piece of rock – the crystal - and a tuning wire with which you scratched the piece of rock to get a shortwave reception on your head phones. Something like that To have a radio was strictly forbidden by the Germans and a great risk, if you were caught.

The Hungerwinter We now had a small potbellied stove in the sitting room, the pipe leading into the chimney of our open fireplace, close to the grand piano. Used for cooking but also the only means of heating.

We now had a small potbellied stove in the sitting room, the pipe leading into the chimney of our open fireplace, close to the grand piano. Used for cooking but also the only means of heating.

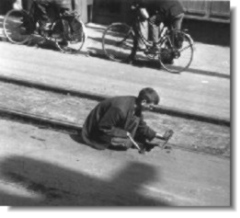

At the end of the war, our, the children's hunger, drove my parents to exchange the grand piano and their gold wedding rings, to provide food for their children. The stove was lit by wood, or if we could get hold of it, cokes. For a long time we had a supply of coal in the cellar for the central heating and where we had also an cold store room. Refrigerators had not come into our lives as yet, before the war. I can still see the "Iceman" who used to come and deliver ice blocks for the cold room, which he carried down into the cellar with an icepick on a piece of sacking on his shoulder. I also remember the rumbling of the coal going down a chute into the cellar. For quite a time, we had a good food reserve there, but finally everything ran out. And the shops finally, in the winter of 1944, had nothing. No milk, no bread, eggs, fruit or vegetables or all the other grocery terms one takes for granted. There was a soup kitchen somewhere, serving a sort of horrible thin vegetable soup. Not exactly filling, but even the soup kitchen ceased to operate at the beginning of 1945. We preserved energy, by lying down mostly. We did manage to steal electricity, I remember, as we had Germans in a house on the corner of our street, a radio post. Also, there was a "sperr" time, a curfew after dark. You could not go out into the street and you had to stay indoors until the next morning. I went on long bicycle rides, on food raids. "Hongertochten" or literally, hunger trips, they were called, to get food. You went to so called "friendly" or "good" farmers to collect wheat. Other "bad" and greedy farmers collected a fortune for their food and as I mentioned, my parents for example, had exchanged the grand piano and gold wedding rings for food. You would cycle for hours in the biting cold and then you stood in long queues for hours in the snow and the cold, to end op collecting perhaps only a pound of wheat. At home, this was ground into flour to make bread with, in a sort of coffee grinder sized mill, screwed onto the window sill. We also desperately ate ground tulip bulbs; I remember you had to take out the green core, which was poisonous, but the cake which was made of ground tulip bulbs was edible in comparison to the raw grated sugar beet boiled into a kind of porridge. Awful stuff, that. It had such an awful taste.

I was once given two bottles of milk by a friendly farmer's wife. I cried for a long time when they broke in my saddle bag on the way home. I practiced a form of meditation when I went on these long and cold bicycle trips. I tried to blot out the miserable cold and discomfort by humming a tune, over and over, so that I could keep going and persevere. I can still remember the tune. It was a tune played by a Dutch jazz band called "the Ramblers".

There was no firewood for heating, trees had been cut down and houses standing empty were emptied of it's timber. Leaving an empty shell of brick. A park in Amsterdam, the "Vondelpark", had been closed at the end of 1944, as almost all the trees in the park had been cut down and stolen for firewood Although it was illegal to be out at night and just as we were secretly going out at night to do just that. I witnessed the cutting down of the trees in the Kalfjeslaan.

The shelters, the Germans had built at Schiphol airfield, were dug out and the wooden frames in them sawn up and distributed.. Schiphol, after those bombardments one of which witnessed by the Professor, had, as I mentioned, been abandoned by the Germans after that final bombing raid on December 13 in 1943. I made sure I was there, to take home my fair share of firewood on my cart. I did not worry about unexploded bombs on the runways I heard about later.

I had a deal with the groundsman of the local hockey club, nearby in the "Bosplan". Among the cinders, which covered the ground underneath the grand stand at the hockey stadium , he picked out good, usable cokes. A terrible job, groveling under the stands in the cinders. I first bought it from him, sacks of cokes, which was for heating, of course, first for our own use but then I bartered the cokes for sacks of potatoes, tins of food and even American cigarettes called "Old Gold", which I then bartered for other foodstuffs. The potatoes were worth far more than the cokes. I think even four times as much. I was doing well.

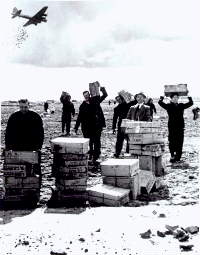

The food drop on Schiphol

After the so called "Hunger winter" of 1944 - 1945 when some 20.000 people died of starvation in Western Holland, the Allies sent in planes. The Americans, the 8th Air force, sent hundreds of B-17 bombers, and R.A.F. Bomber Command, sent hundreds of Avro Lancasters to drop food at Schiphol, and also a great number of other "dropping zones" in still occupied Western Holland. . I "helped", collecting the food and I had positioned myself on a barge in the canal - the "Ringvaart" - adjoining the airfield.. Others came to offload the sacks of food they had collected on the fields and runways, loaded on primitive vehicles. I helped off load the sacks into the barge. I remember the tins of butter, burst open and the sacks of sugar and broken tins of bacon. Dipping my fingers into the butter and the sugar, I gorged myself on this as well as scooping and eating the bacon out of the broken tins. Everybody else did the same thing. Gorgeous. The RAF had dropped tins of hard biscuits - emergency rations - and tins of corned - "bully" - beef. I came to love corned beef. Everything was subsequently distributed. Soon after, we also got rationing tickets to collect so called "Swedish bread", bread made from Swedish flour. Originally I thought that the loaves had also been dropped by air but it is only recently that I found out that the bread was made from the flour, the Swedes had sent by ship. Beautiful white loaves. We also got margarine to go with it. You can't imagine what a glorious taste a slice of that white bread and margarine had. You had to stand in a long queue at the bakery shop to collect your bread rations. But you didn't mind. Thank you again, Sweden.

After the so called "Hunger winter" of 1944 - 1945 when some 20.000 people died of starvation in Western Holland, the Allies sent in planes. The Americans, the 8th Air force, sent hundreds of B-17 bombers, and R.A.F. Bomber Command, sent hundreds of Avro Lancasters to drop food at Schiphol, and also a great number of other "dropping zones" in still occupied Western Holland. . I "helped", collecting the food and I had positioned myself on a barge in the canal - the "Ringvaart" - adjoining the airfield.. Others came to offload the sacks of food they had collected on the fields and runways, loaded on primitive vehicles. I helped off load the sacks into the barge. I remember the tins of butter, burst open and the sacks of sugar and broken tins of bacon. Dipping my fingers into the butter and the sugar, I gorged myself on this as well as scooping and eating the bacon out of the broken tins. Everybody else did the same thing. Gorgeous. The RAF had dropped tins of hard biscuits - emergency rations - and tins of corned - "bully" - beef. I came to love corned beef. Everything was subsequently distributed. Soon after, we also got rationing tickets to collect so called "Swedish bread", bread made from Swedish flour. Originally I thought that the loaves had also been dropped by air but it is only recently that I found out that the bread was made from the flour, the Swedes had sent by ship. Beautiful white loaves. We also got margarine to go with it. You can't imagine what a glorious taste a slice of that white bread and margarine had. You had to stand in a long queue at the bakery shop to collect your bread rations. But you didn't mind. Thank you again, Sweden.

For us liberation came on May 6, 1945. One day after the formal capitulation by the Germans.The food droppings continued for some time. Road transport followed, to bring more food and Rotterdam was again open for shipping.