2000 loaves of Bread - Manna from Heaven

I am one of the many Dutch people who benefited from the food drops.

As a young boy I remember the Lancasters swooping over our rooftops to drop their precious cargo on a sports field not far from my home in The Hague.

The crews had made little parachutes out of handkerchiefs with sweets and their RAF badges on them to be dropped off before the "manna" was delivered.

I am sure that this heroic humanitarian act by the Allies saved the lives of countless Dutch people at the time and the efforts of the pilots and crew are appreciated very much by the Dutch people - wherever they may be.

I am sure that this heroic humanitarian act by the Allies saved the lives of countless Dutch people at the time and the efforts of the pilots and crew are appreciated very much by the Dutch people - wherever they may be.

The Dutch famine of 1944, known as the Hongerwinter ("Hunger winter") in Dutch, was a famine that took place in the German occupied northern part of the Netherlands, especially in the densely populated western provinces above the great rivers, during the winter of 1944-1945, near the end of World War II. A total of 18,000 people died during the famine.

Under the cruel German regime more than 3 million people in the cities suffered and went without food, heating, electricity, medication, transport and in some cities where even the taps ran dry.

Food was rationed but not available in the shops, however, one could exchange food coupons to obtain a daily meal from so-called Gaarkeukens (soup kitchen, a bread line, or a meal centre set up by the Councils) where a watery cabbage and potato soup would be served.

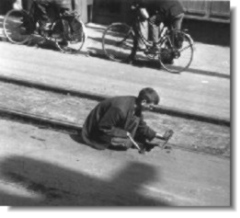

Trying to find food people travelled long distances under harsh winter conditions into the country bargaining with farmers for anything eatable.

As an alternative people ate tulip bulbs which were still available on the black market; once world-famous tulip brands such as the "Darwin" and "The City of Haarlem" ended up in cooking pots instead of flower pots.

Sugar beets were chopped up and boiled, the syrup used on bread and the pulp made into a sort of pancake.

Fuel for heating and cooking was no longer available and people started to cut down large numbers of trees in parks and streets , or worse, starting to burn their floorboards, doors and wooden fences. Deserted or un-occupied dwellings were demolished very quickly for their timber and although police tried to prevent this they only found rubble when they returned to the scene.

Fuel for heating and cooking was no longer available and people started to cut down large numbers of trees in parks and streets , or worse, starting to burn their floorboards, doors and wooden fences. Deserted or un-occupied dwellings were demolished very quickly for their timber and although police tried to prevent this they only found rubble when they returned to the scene.

As the situation worsened the German occupation allowed the Swedish Red Cross to ship flower into Holland during the first week of January 1945. That gave the starving population again a few more days of survival.

The reason for this wretched situation was the decision made by Seyss-Inquart, the German Reichskomissar for the occupied Netherlands, that his only concern was for his struggling German people and that the German army had to take everything that the Netherlands still had to offer.

After some time it became clear to the obstinate German authorities that they were not fighting for their lives anymore but for a lost cause instead and permission was granted to start "food droppings" for the starving population of the western part of Holland.

The Allies had already started to make arrangements on the 29th of April 1945 for the supply of food by air knowing that every day of delay would be fatal for many.

That day Lancasters of the R.A.F in England took off and dropped 600 tons of groceries comprising potatoes, flower, peas, beans, yeast, canned beef, sugar, margarine, cheese etc. enough to relieve the most urgent needs. The day thereafter 450 Lancasters carried more than twice the load of the previous day.

In May the United States also started to take part in the food drops, 400 Flying Fortresses carried 36,000 U.S. Army rations to the starving Dutch. Such an Army ration consisted of beans, biscuits, bacon, sausages, milk, coffee, sugar, butter and other items fit to eat. The R.A.F. added another 1800 tons to that amount.

In May the United States also started to take part in the food drops, 400 Flying Fortresses carried 36,000 U.S. Army rations to the starving Dutch. Such an Army ration consisted of beans, biscuits, bacon, sausages, milk, coffee, sugar, butter and other items fit to eat. The R.A.F. added another 1800 tons to that amount.

One day later, on the 2nd of May, there were at least 900 big aircraft flying over Holland that jointly dropped 1600 tons on drop zones in the neighbourhood of Amsterdam, Alkmaar, Hilversum, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht.

Again, on the 3rd of May, another 800 tons of food was carried by 400 U.S Air Force B-17's.

General Eisenhower also ordered road transport to commence and 120 trucks loaded with groceries and fuel arrived in the German occupied part of the country.

Medical teams stood in readiness to attend to those who were seriously ill.

No food dropping missions were flown on the 4th of May because of poor weather conditions, in the following three days the aircraft appeared again in large swarms over occupied Holland to deliver their cargoes.

On May 5th 1945 British and American aircraft flew for the fourth time to Holland since the start of the food droppings. They arrived half an hour after the Germans had unconditionally surrendered and the liberation of the Netherlands became a fact.

Between the 29th of April and the 8th of May 1945 R.A.F Bomber Command dropped approximately 3,100 tons of food, the 8th U.S. Air Force delivered 8,450 tons of groceries to occupied Holland which is the equivalent of 11,500,000 excellent meals.

Lancasters of the Australian 460 Squadron dropped approximately 300 tons of food during this period in the more heavily populated areas of Amsterdam and The Hague.

MY HUNGER WINTER 1944

I still have strong recollections of this terrible time. In 1944 I was a young, thirteen year old boy who lived with my parents and baby sister in Voorburg, a small town on the outskirts of the city of The Hague.The Germans invaded the Netherlands in May 1940 and occupied our country.

As the Allies moved towards Germany only the southern part of the Netherlands was liberated. The western part of the country, better known as Holland, remained under Nazi control and resistance by Dutch partisans grew day by day. The railway workers went on strike and in retaliation the occupying forces stopped supply by rail and any distribution of food to the population.

Early 1944 all males over the age of sixteen were picked up and forced to work in Germany; many could evade this forced labour and went underground.

Unfortunately my father was caught and sent to Lübeck to work in the Dornier aircraft factory. We never saw him again until after the war finished and the Germans surrendered in May 1945.

The German military not only dragged our fathers and brothers away, they also stole the food intended for the remaining population in Holland. The result was famine!

Fortunately we were not famished, we had enough food. As early as 1943 my Dad had worked in the province of Zeeland and was able to provide us every month with goat and sheep meat, wheat, butter and cheese when he came home on leave.

Of course things changed when father was taken away. Nevertheless, my mother had a linen-cupboard full of beautiful new bed sheets, pillow slips, towels, etc. that could be traded for bread, potatoes, butter and sometimes meat.

This black market trade was arranged through a well known local identity, well entrenched in this illegal trade. Mum and my little sister would go and negotiate with him and his wife and often they were asked to stay for lunch or dinner. Remember, if you are hungry it is easy to swallow your pride and it must be said that these people meant well.

Ultimately the linen-cupboard was empty and trading the family silver for food was the next option.

The German army had started a drive to collect brass and copper, iron and steel to smelt into weapons and collect blankets, warm clothing and furs for their soldiers at the Russian front. Donation was compulsory and the soldiers knocked on every door.

One day my little sister opened the front door and noticed this rueful grandfather in German uniform standing there. When he saw this little girl his emotion got the better of him and with tears in his eyes he told my mother his sad story. He did not agree with the orders that were given him, when he saw my little sister he could only think of his own grandchildren and certainly not of copper or fur.

That's how we kept our copper ornaments and plates; fortunately the family silver saw the end of the Hunger Winter and it stayed in the side board!

Some years later when Mum told me to polish the brass and copper ornaments and plates I told her I didn't like the job and that I wished the Jerry had taken her brass and copper. For that smart comment I got a good clip around the ear from her.

Coal, kerosene or town gas was no longer available, cooking or heating was not possible that way.

Consequently practically every tree in the neighbourhood was cut down for fire-wood and kindling used to fuel a so-called Majo stove. The Majo stove was only a 30 cm high, 20 cm dia. tin can, open on both ends with a diagonally supported inner metal tube where paper, kindling and wood slivers were burnt. The Majo stove itself set on top of a potbelly stove where the chimney provided the draft, this system created good heat for cooking but it consumed fuel at a fast rate.

Once the supply in the neighbourhood ran out we had to go further afield to find trees.

With Annie, the daughter of friends, and armed with an axe, saw and a pram to carry the loot we sat out for Wassenaar, some 12 km as the crow flies from Voorburg.

It was bitterly cold and such a long way but we found a couple of small birch trees that we sawed and chopped till we had enough to load the pram.

Happy with the result we went home; by then it was dark and snowing with temperatures way below freezing point.

Half way home I broke down and burst out in tears because I was so cold and miserable. Annie, as only a woman can do that sort of thing, talked to me and gave me courage and strength to push the pram home.

The experiences of that day have never left me. Even well before this episode I used to tell my Mum that when I grew up I would go where it is nice and warm, I certainly did that when my work took me to the tropics!

Even now I can't stand the cold and feel miserable when the temperature drops below zero or after a few cloudy days.

John Papenhuyzen December 2010